Prisoners of Fire - Part I: Surviving the California Inferno

Pacific Palisades, CA, January 7, 2025: Imagine you are running for your life in gridlocked traffic as the flames close in.

(Author's note: This is the lead-off to a two-part report about the destruction-by-wildfire of a Southern California community last January, and the long slog towards recovery-- even as the Trump administration trashes climate change science and vital safety nets. Welcome to the future in MAGA America.)

If you’re looking for the worst possible place to mount an emergency evacuation under crisis conditions, Pacific Palisades, California would rank near the top of the list.

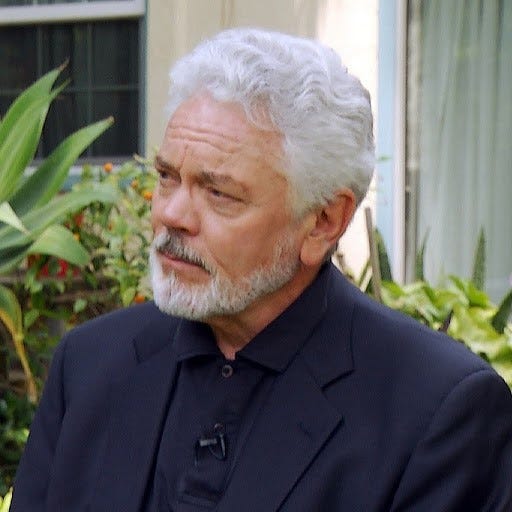

I speak from experience. I was one of the last CIA officers to be airlifted out of war-ravaged Saigon on April 29, 1975. And I beat a hasty retreat from the Palisades with my family in tow during the first hours of the inferno of January 7.

Both escapes were more harrowing than I care to remember – and often for the same reasons, a lack of sufficient evacuation planning and early warning bells and a shortage of ground-level personnel to handle simple traffic control.

In case you don’t know the area first-hand, the Palisades, in its pre-fire prime, was an ultra-upscale community of 20,000, nestling comfortably up against the Santa Monica Mountains like a reclusive dowager with a well-developed superiority complex.

It was home to my own very down-to-earth 22-year-old daughter Paige and her valiant 63-year-old mom, who prefers to be identified simply as June.

Thanks to overly protective town planners dating back to the 1920’s there had never been an easy way to get into and out of the Palisades unless you owned a helicopter or wind glider. The one main artery, the last leg of storied Sunset Boulevard, arrives out of a tony LA neighborhood to the east, meanders through Palisades Village proper, and dead ends at Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) next to the beach nearly three miles to the west.

Even in the best of times, traffic along sections of Sunset in either direction could suddenly become spasmodic and accordion-like for no good reason. The jam-ups were particularly acute in the Village itself, a patch of good taste and bad, high-end retail stores intermingled with struggling mom-and-pop operations, two massive groceries, three gas stations, a Tesla recharging center and a car wash. On any given day, maddened minivans and adrenalized muscle cars dueled for running room amid these staples of suburban living -- and never so frenziedly as during the daily rush-hour periods, eight-to-ten and four-to-six.

God help you if you ever got caught out in one of these free-for-alls and needed to get somewhere fast, like an ER unit. Your best hope was just to jump out of your car and run.

If you were willing to endure eccentric traffic lights and merciless intersections, there were ways to avoid Sunset altogether and jump down to PCH in less time than a fatal heart attack.

One of these, a still viable little two-laner, splits off from Sunset just east of the Village, creeps past gated mega-mansions typically flush with pretense and flammable foliage, and slides into a terrifying four-way intersection at PCH.

Its parallel westside counterpart, Temescal Canyon Road, spills out of a parking lot next to a mountainous recreation area dear to hikers, cuts across Sunset, morphs into four-lanes, sideswipes Palisades High School, which my daughter once attended, and finally dumps into PCH about a mile away.

During the first day of the fires, Temescal served briefly as an escape route for evacuees, then became a roam zone for wind-swept embers and burning debris looking for something to incinerate.

My daughter’s alma mater was an early casualty, part of its campus quickly reduced to a hellscape of gnarled, flame-savaged girders,

As an integral part of LA (not a separate incorporated town), the pre-fire Palisades imported cops from an LAPD station seven miles away via Sunset, with only one patrol car assigned permanently to the community.

In normal times, the shortage of local law enforcement brought out a certain libertarian bravado among many locals – and served as a beckoning finger to bank-robbers, looters and anyone who might want to make a quick getaway without being noticed. On Day One of the inferno, this mindset gave way to a more singularly focused one. I wouldn’t label it “every-man-for-himself,” but it was close: an obsessive determination to get your very own family to the head of the evacuation lines.

As per long-standing protocols, two on-site fire stations serviced the community, one of them located inside the Village itself, the other plunked on a corner far down Sunset, near its outlet to PCH.

The equipment and fire trucks at each station were always spit-shined and ostensibly up to date.

But they were only as deployable as traffic on Sunset allowed.

And that, dear reader, is why everything went to hell in a hand basket once the flames arrived.

Theoretically, in any fire emergency, the LAFD can summon helicopters and modified aircraft to drop water and chemical suppressants onto the blaze. But in this firestorm, ferocious Santa Ana winds grounded many such flights, especially during the predawn hours of the second day.

There was another major handicap, this one involving topography. Since much of the Palisades sits atop an elevated plateau, with many of the priciest homes clinging to lofty hillsides, it takes highly pressured water to keep fire hydrants fully primed and functioning.

Guess what happens when every building in sight requires full-volume hose-downs amidst hurricane-force winds?

Hydrants lose pressure and dribble dry, and heavily engaged firefighters must draw directly from the trunk lines running from three locally dedicated water basins, thus further diminishing supply and pressure readings.

As backup, to supplement the flow, firefighters can bring in mobile water tankers as happened in the Palisades and four other fire-ravaged communities in the far-flung LA area.

But maneuvering such equipment into position can become ever more arduous as the flames approach, and the crews’ own exposure increases exponentially until retreat is the only alternative to being burned alive.

What happens then?

What happens is emblemized by the Palisades fire.

Call it Nature’s vengeance, the deadly upshot of climate change. Its hallmark is rapidly intensifying multi-front wildfires fed by unprecedented winds whipping through multiple sections of a community all at once, then quickly engulfing other communities, each new extension further straining resources designed to handle individual structural fires only, not entire regions going up in flames.

During the Vietnam war Peter Paul and Mary immortalized a mournful lament about lives lost and those who bore responsibility. It ended with the aching refrain: When will they ever learn?

Those words ring as true today about the climate crisis and those enabling it, fact-averse billionaires whose devotion to fossil fuels is driving global temperatures to the point of instant combustion.

When will they ever learn?

Escape – January 7

On the night of January 6 or perhaps in the wee hours of the next morning, the first major sparks of the Palisades fire dropped somewhere on a sparsely populated hillside east of Malibu, possibly behind a private residence on Piedra Morada Drive, which overlooks a heavily wooded arroyo.

At the time I was snoozing peacefully in June’s downstairs guest room as she and my daughter, Paige, chased post-holiday dreams in newly renovated quarters upstairs.

A few hours later, at about 8:15 am, a hiker detected a smoky odor near Skull Rock on Temescal Ridge Trail only a quarter of a mile, as the crow flies, from where we were.

By then we were dawdling over breakfast – under clear skies.

But by mid-morning, from June’s front window we could make out a sickly yellow pall congealing above the Pacific. On Marquez Avenue, the side street just below the hillside cul de sac where June’s elegant home had aged gracefully for seventy years, traffic was thickening.

Shortly after 10 am, while I was thumbing my Samsung searching for news, a spry 89-year-old neighbor banged on June’s front door to ask if we’d heard the advisories about an approaching firestorm and the need to prepare for an evacuation.

Since experience and age have made me a slow-burn alarmist, I brushed aside the old guy’s queries as an addled imagination getting ahead of itself. But an hour later my mood and the facts changed dramatically. Paige and her mom returned from a reconnaissance of a nearby cross street and reported roiling flames and smoke closing in on a neighbor’s house just one small hillside away. A short while later, at 12:07, a mandatory evacuation order from fire and police authorities pinged on June’s iPhone.

That did it. Paige ducked into the backyard to say a prayer over the grave of my cherished shih tzu Maltese, Peanut, who had succumbed to cancer last summer. Clearly visible above the flanking hedgerow, another wedge of flame was slicing into the middle distance.

The three of us then headed for the curb out front, and after trying unsuccessfully to persuade our aging neighbors to join us, piled into my old Highlander, June sliding into the backseat and Paige assuming the co-pilot’s position, with her GPS app at the ready.

I then grabbed the wheel and launched us towards the only available exit, the small cross street at the end of the block where the two of them had spotted the approaching fires. Pausing only briefly at the turn, I swung a hard left, away from the flames, blew past some kids who were using their iPhones to preserve memories of the spectacle, and then hung left again onto now traffic-choked Marquez Avenue.

Two blocks ahead lay a feeder lane into Sunset. I figured our best bet was to bear east at the adjacent intersection and follow Sunset all the way to Temescal Canyon Road, the nearest and fastest access route to PCH.

But twenty minutes later we had barely moved a car’s length, and not a cop anywhere in sight to break the logjam. Paige, checking her GPS, reported traffic movement on lower Sunset. Praying she had it right, I wheeled the car around, sped west on Marquez, miraculously finding an open lane. It carried me all the way to an alternate exit, a three-way crossroads feeding into lower Sunset.

Edging past a Tesla truck whose bulk partially concealed what lay ahead, I slid into the outer westbound lane, hoping to ride it straight down to Sunset’s own terminus at PCH. But barely had I traveled a few yards before I realized, to my horror, that traffic in both directions was fusing into a solid mass.

Fearful of being hemmed in, I nudged towards the center divider so I could swing around and head back the other way if and when the crush loosened. Outraged motorists honked, howled and showed me the finger.

A short distance ahead, Sunset tipped into a gentle incline, a meandering stretch of roadway that led past the second Palisades fire station and the single turnoff from the Highlands, an affluent mountainside community where smoke was already crawling along the ridgeline

As I inched towards the slope, Paige, whose instincts and eyesight are better than mine, suddenly cried out that fire had just leapt ahead of us. June gasped in alarm. In the same instant, a wave of flame rose up out of the Highlands and broke towards the fire station a half mile ahead.

Jerking the wheel, I swerved left through the opposing lanes, bounced off the curb, and pulled into a U-Turn --- only to find us again stuck in place.

A fire truck trapped somewhere in the mire wailed incessantly, but no one had any room to give space.

For a moment I had the overwhelming impulse just to ditch the car and launch us into a desperate sprint. But in the same instant I noticed a tiny road off to my right with a "No Outlet" sign posted at the entrance.

June saw it too and urged me to take it. It so happened that her eight-year-old grandson had recently speculated to her that this was a shortcut to the beach.

Paige, keying off her GPS, insisted it was.

I hesitated, not wanting to get us sandbagged in some flame-ridden back alley.

But then abruptly, as if by a miracle, four police cars with sirens screaming loomed up out nowhere, cut across Sunset in front of us and zipped into the little roadway.

I hit the gas and followed.

In a breath, we were barreling down a deserted two-laner so shrouded in foliage there was no telling where we were headed. On a count of fifteen, even as I was about to jam the brakes, we shot into a clearing.

It looked, at first glimpse, like some wildcat developer’s dream gone bust, abandoned vehicles in various states of repair sitting at odd angles to seemingly distressed bungalows. But just a few yards in, the road abruptly slipped into a downhill turn, and I eased into it. Seconds later a police cruiser lunged up from the opposite direction --the cop at the wheel wearing a thousand-yard stare -- and swept past without breaking speed. I felt a prickle of dread, expecting to see flames leaping after him. But just as abruptly, the concourse flattened out, emptying us into the parking lot of a swanky private beach club.

Catch your breath, let your heart settle, I kept telling myself. I had once crashed a dance party here, and though the clubhouse was now deserted, I remembered that a little connector lane extended to the beachfront. Paige’s GPS confirmed this.

Scanning the parking area, I found the outlet and beelined for it. In moments I was coaxing my Highlander into an intersection on PCH.

Across the way, rollers undulated along the break-line amidst drifting smoke.

Paige and her mom were, in Paige’s words, “freaking out” from frayed nerves. I felt positively ill.

PCH was nearly deserted, at least in this particular section, perhaps because barricades had been thrown up further north near Topanga Canyon or Malibu.

I slipped into a southbound lane and made for the 10 Freeway into Los Angeles where I had an apartment.

A half mile on, I passed through an intersection manned by the first traffic control personnel I’d seen all day. It was the junction of Temescal Canyon Road and PCH, my original destination at the start of this hellish odyssey.

Lines of idling vehicles extended all the way up Temescal towards Sunset and Paige’s former High School, each car or minivan packed with evacuees, each driver waiting to be beckoned forward.

Part of this corridor and the school itself would soon be stalked by flames. So too, the “private” little escape route we had followed to safety.

Meanwhile at various other choke points, including the lower section of Sunset where we had nearly stalled out, people who had waited too long were abandoning their vehicles and running for their lives, with fire licking at their heels and too few police or traffic controllers to provide help.

Once we’d cleared the McClure Tunnel, June phoned our aging neighbors and, finding them still at home, begged them to head for our “No Outlet” escape route without delay. They would flee much later that afternoon, via Temescal and PCH.

Waiting for Word – January 7–25

After the mass evacuation of the Palisades on January 7, it took firefighters three days to bring the mega-blaze under control, and another two weeks before the area was deemed safe enough for sustained civilian visits.

In the meantime, time lost all shape for those of us who had fled. Sleep became a stranger. From January 7 to the 25th, my family and I lived in a kind of purgatory, delivered from the flames but never free of them.

The first several nights, Paige and her mom sheltered in my cramped one-bedroom apartment in West Hollywood. Paige was battling a worsening kidney infection. June teetered on the edge of exhaustion. From the foyer of my building, we could see a fiery glow above the Hollywood Hills and wondered if we might soon be on the run again.

Disaster coverage was nonstop, but the reporting was muddled, offering little clarity about what was happening along the fire lines. The earliest images from the devastated communities evoked Dresden after the firebombing or Hiroshima at ground zero. But overwhelmed reporters misidentified neighborhoods and mislabeled ruins, lumping the Palisades together with Altadena, Pasadena, and Malibu, offering no distinctions. The jumble of footage made it impossible to know what had survived.

On three separate occasions Paige called the LA Department begging for help in saving June’s home. Each time she was assured that an advisory had been relayed to fire crews in the area.

Our first real smattering of news about June’s house came from a neighbor’s blurry online photo, which seemed to show an intact roofline. But this was only the second or third day, while the neighborhood was still burning, so any judgment seemed premature.

A more promising sign came from June’s little Tesla, which she’d left parked just across the street from her home. Throughout the firestorm and for many days after, its sensors kept sending temperature readings to her phone. Only once—briefly on the second day—did the temperature spike above the mid-seventies. In the vacuum of reliable information, this tiny signal dared us to hope.

On the third day, we visited a FEMA relief center in a Westside municipal building, looking for donated clothes. All we could find for the diminutive June was a pile of tattered T-shirts and shorts that looked like teenage fashion statements. In another time we might have laughed. Not now. June shook her head sadly and vowed to keep wearing, for as long as possible, the clothes she had escaped in. At least there was dignity in that.

Almost every staffer and volunteer we encountered at FEMA locations in the area seemed well-intentioned. But many were clearly overwhelmed, undertrained, and unfamiliar with their own protocols. Their generosity, hastily mass-produced, had a take-it-or-leave-it quality that reminded us constantly we were beggars at the trough. Congenitally upscale Palisadians, who had never waited in line for anything, now patiently fell into step with the rest of us and gratefully accepted second-hand blankets and flip-flops and any help they could get in filling out disaster forms.

On the fifth day, our own fortunes brightened. Satellite maps confirmed what the Tesla signals suggested: the worst of the fire had leapfrogged June’s two-story L-frame. Grainy images revealed enough structure to cast shadows. Nine other houses on her street seemed intact too.

But as the satellite imagery filled in, it also became clear that much of Marquez Terrace had been torched. Seventeen neighboring homes, including one just two doors away, were just blackened outlines. A cluster near the lone intersection had collapsed into smudges, along with many estates on the flanking hillside.

Finally, amidst this jumble of mixed signals, a neighbor three doors down showed up online to provide some clarity. By his account he and his son, joined by friends, had stayed behind the first two days and tried to save their own homes and nearby one with garden hoses and urgent appeals to passing fire crews. In other neighborhoods too, similar volunteer brigades had backstopped overextended professional firefighters.

The neighbor sent us photos of June’s house—or parts of it. One showed water leaking from under her garage door, proof the front still stood. Another featured someone, likely from the neighbor’s group, hosing down the rear hedge. Yet another revealed the back wall of June’s house looking relatively unscathed.

But the pictures, like the satellite images, were inconclusive—fragmentary snippets with imperfect timestamps. Missing were wide angles of the front or sides of the house. In one sequence, the rear shrubbery, which had appeared intact in the “hosing-down” photo, looked badly singed, suggesting that subsequent events had overtaken that more hopeful moment. The ambiguities were maddening.

At the end of the first week, we were heartened to learn that authorities had decided to allow for brief escorted visits to the fire zone by residents with proof of address. But the hurdles were daunting. You had to rise before dawn, hike miles to a checkpoint, negotiate with security, then—if cleared—catch a police ride for a five-minute glimpse of your home, or its ashes.

Every time we tried, we were turned back. On January 11 the visitation policy was abruptly terminated. Officials cited lingering hotspots, downed lines, and toxic debris. But it’s also possible they wanted to head off any public reckoning over what had been left undone before, during, and after the fires.

So, we kept waiting, obsessing over every revised FEMA advisory, every vague LAFD handout, every blurry satellite image, every scrap of information from online support networks.

By the third week, FEMA had agreed to cover a hotel room for June near my apartment. But no one at the agency could tell her whether her stay would last a day or a week. The uncertainty was torture. Thousands of other fire survivors found themselves similarly adrift.

Meanwhile, Paige’s compassionate leave expired. On January 23 she flew back to New York to resume work. Sad though I was to see her go, I hoped distance might bring her some relief. Her reserves were spent. More than once, she’d told me the fire had stolen her childhood, and I knew what she meant. The landmarks were gone—her kindergarten around the corner, much of Marquez Elementary, a large swath of Pali High. Even if her mother’s house had survived, the home it had represented as a source of comfort, safety, and identity was hopelessly violated.

Paige shed few tears when she left. She just withdrew into a remoteness that was becoming all too familiar.

My own grief had its own undertow. I had lived this before in Saigon, 1975, watching a country collapse into fire and oblivion, people clawing at helicopter skids to escape.

Age helps, of course. At nearly eighty-three, I’d learned how to metabolize disaster, or at least hold it at arm’s length. Still, Paige’s losses were mine too.

So were her mother’s. During those first three weeks, I agonized constantly about her. But June refused to dwell on her own hardships. As she later told me, she was already struggling with “survivor’s remorse”—a nagging guilt that some part of her home might be salvageable while so many neighbors had lost everything.

(See: Frank Snepp 360, “Prisoners of Fire -- Part II: Emerging from the ashes.”)

I don’t think I’ll ever forget the moment my daughter woke me to say the flames were behind the Lutheran church across from our apartment. We picked up whatever clothes were on the floor and our dog and his food and headed away , meeting incoming firefighters. We lived in 7 hotels and just returned August 1. Our unit was closed because of asbestos and Lead . Not found by FEMA months before.

I’m suffering from horrible asthma and my daughter now takes a 2 hour bus ride to Tarzana since her job at Atria suffered so much damage.

We are looking to move but the world as it exists here is too mentally unstable.

We have met many wonderful kind people on this journey from Woodland Hills to West Hollywood.

I wish for you all to find stability and peace. So happy Paige could escape to her own reality and quiet .